Youth medical gender transition is widespread in New Zealand

In Wellington, the rate of medical transition is similar to the rate of serious traffic injuries

A brief summary of this article was published in The Standard. An adapted extract from this article was also published in Plain Sight.

Many New Zealand children have started identifying as transgender, and some are being prescribed powerful drugs and hormones. New Zealanders have noticed this trend, and quiet concern is widespread. Many people are unconvinced that these children need to be medicated, and would prefer that they were offered alternative forms of support. A recent Curia survey found that 42% of New Zealanders support a total ban on puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones for children aged under 18, while only 36% oppose such a ban. Support for a ban is strongest among parents of young children and adolescents. Many people who oppose an outright ban on youth transition nonetheless favour a cautious approach. Yet there are signs that current medical practice may be severely out of step with public opinion, with Newshub reporting that some New Zealand doctors are offering puberty blockers to teenagers within ten minutes of meeting them.

Rushed medical transitions can have tragic consequences for vulnerable young people. One example is the story of Zahra Cooper, as told by the New Zealand Herald in a compelling video documentary. Zahra is a young New Zealand woman who “after searching the internet and watching YouTube videos about transgender people... realised she felt... like she was trapped in the wrong body”. She was assessed by a psychiatrist, who failed to detect her autism spectrum disorder. Her psychiatrist diagnosed her with gender dysphoria (a clinical term for profound discomfort with your biological sex).

Zahra started taking testosterone to treat her gender dysphoria. Instead of improving, her mood worsened significantly. Her endocrinologist failed to follow up on her progress, and she attempted suicide twice. She realised that gender transition had worsened her mental health. She decided to stop taking testosterone, and her distress abated. She was, however, left with a permanently deepened voice. The damage her course of testosterone may have caused to her long-term health is unknown. She is still often mistaken for a man, which she understandably finds frustrating and distressing.

An article in the New Zealand Listener tells a similar story. A young Kiwi woman, who uses the pseudonym “Rachel”, started taking puberty blockers at age 14. She was prescribed testosterone shortly afterwards, and had her breasts surgically removed at age 16. She had her womb removed at age 18. By age 22, she was “swamped by regret”.

Rachel now says, “It was almost like I woke up from a weird dream - what was going on? Transgender ideology stopped making sense to me and I thought, ‘Wow, with time and the right support, I could have lived perfectly happily as a masculine lesbian woman’”. Her medical treatments have left her permanently medically dependent on oestrogen. She will live with the consequences of her surgeries for the rest of her life.

In another similar article, a New Zealand mother explains that her child “met some trans people online on a gaming site”. Suddenly, her child started identifying as transgender. She felt that her child was subsequently rushed into medical gender transition:

I told the doctor at the clinic about my concerns, the suicide of my son’s father when he was four, the depression in his wider family, his [autism spectrum disorder]. It made not a whit of difference. He received no counselling, just affirmation.

In what reports from within the trans community suggest is a recurrent pattern, after transitioning, her child broke off all contact with family and friends:

I have neither heard from nor seen him since. He doesn’t reply to texts, phone calls or letters. I am bereft. I lie awake at night and think of the funny little boy I raised and my heart breaks. He has not only cut me out of his life but others close to him as well; his Big Buddy who has been his mentor since he was seven, his music teacher, his older brother and sister who live overseas. I assume that he is being influenced by others. I know that activists tell kids that if their parents aren’t 100% on board with their transition they should be excised from their lives.

He and I have been through so much together in the past fourteen years and I never imagined that something like this could happen to us.

I saw this mother speak at a recent conference, and it was heartbreaking. But are these stories just isolated incidents, or signs of a much larger medical tragedy?

Overseas, the ‘trans wave’ is well-documented. Numerous children and young people have undergone controversial and life-changing medical interventions. Stories of regret are widespread. Researchers and practitioners have strongly criticised the lack of safeguarding when treating gender questioning children. The international news media has repeatedly highlighted the risks of medical transition. Documentaries like What is a Woman?, Mission Investigate: Trans children, and Affirmation Generation have brought the issue to public attention. In Australia, a poignant 60 Minutes documentary about the perils of transitioning young patients has been viewed over three million times on YouTube alone. This prominent media coverage has made the harm done by the reckless medicalisation of children difficult to ignore.

In contrast, in New Zealand our mainstream media reporting on trans issues is often restricted and one-sided. This makes it hard to find reliable information on how these issues are affecting our country. Perhaps as a consequence, some New Zealand parents believe that the trans wave is unlikely to affect them personally. The extent of this issue is hotly debated on social media, usually in the absence of any solid evidence.

How realistic is it for a New Zealand parent to worry that one of their children might be caught up in the trans wave? We can break this question into two parts:

How many people identify as trans?

How many people medically transition?

The answers to these questions are likely to be different but linked. A 2014 study in the Netherlands asked people who identified as trans whether they wanted to medically transition. Among males, about half wanted to transition. Among females, about a quarter wanted to do so.

While evidence on how the trans wave is affecting New Zealand is fragmented and has not been widely reported, it does exist. Let’s look at the evidence on medical transition first, then at trans identities.

How many people medically transition?

Medical transition is sometimes euphemistically called ‘gender affirming care’. For young patients, the first step is taking drugs called ‘puberty blockers’. These drugs artificially stop many of the sex-specific developmental changes that usually occur during adolescence. They are followed by opposite-sex hormones, which cause the patient’s body to develop some of the physical characteristics typical of the other sex. The final step is surgery, which reshapes the patient’s body and sometimes their genitals, with variable results.

In New Zealand, puberty blockers and hormonal treatments appear to be readily available. According to Newshub, the government’s most recent budget included NZ$2.2 million to publicly fund these services, and NZ$2.5 million to train family doctors in “advising trans youth”. Counting Ourselves, a 2018 survey of people identifying as trans or non-binary, found that 81% of those who had asked a doctor for cross-sex hormones had been prescribed them. A University of Otago epidemiologist has reported that many New Zealand health professionals are concerned that puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones are being overprescribed. Worryingly, she says that most of these health professionals are afraid to speak out publicly.

Trans medicine in New Zealand may not always meet basic safety standards. These standards require “mental health support and comprehensive assessment for all dysphoric youth before starting medical interventions”. This support helps ensure that people who transition enter the process with realistic expectations and sound insight into their own motives. Both these factors are key to a successful outcome. If done properly, a careful process of assessment and exploration takes months or years to complete. Unfortunately, pre-transition mental health assessments in New Zealand may often be perfunctory or non-existent.

A 2019 study found that ‘gender affirming care’ was available without a mental health assessment in several regions of New Zealand. Counting Ourselves likewise found that under half of respondents had received a mental health assessment. Often, this was because they didn’t know where to go or couldn’t afford it. This lack of safeguarding appears to be getting worse due to activist pressure to remove perceived barriers to transition. Activists claim that patients themselves can accurately determine whether they will benefit from medical transition, but this is demonstrably false. Multiple examples suggest that the removal of proper safeguards can lead to transition regret.

Even in regions where mental health assessments exist, they may not always be effective. The activist group Gender Minorities Aotearoa explains that if you need to ‘pass’ a mental health assessment “you can probably guess the ideal answers”. They also explain exactly what those ideal answers are. For example, they advise readers to “be sure to tell your healthcare provider how positively HRT [Hormone Replacement Therapy] will impact your life” and “let your provider know that you understand all the possible effects of HRT”. They additionally suggest that “it may help if they know it’s not a passing idea - if you’ve felt this way for a long time, tell them”.

Gender Minorities Aotearoa also remark that in New Zealand, the standards for ‘passing’ a mental health assessment are quite relaxed, explaining that “none of the less ideal answers should prevent you from being prescribed HRT. The only ‘hard nos’ are hormone-sensitive cancers (such as testicular or cervical)”. Consistent with this advice, the Guidelines for Gender Affirming Healthcare for Gender Diverse and Transgender Children, Young People and Adults in Aotearoa, New Zealand state plainly that “having… mental health concerns does not mean gender affirming care cannot be commenced”. The booklet Supporting Aotearoa’s rainbow people: A practical guide for mental health professionals is even blunter, advising clinicians that “Health professionals should trust the self-determination of an individual and that they know what’s best for them when it comes to gender-affirming healthcare”.

A brief investigation of the information provided to young patients provides little comfort. Auckland’s youth medical transition service promises patients that they “recognise that you are the expert when it comes to your gender”. They describe their initial assessment as “a 90 minute appointment where we get to know you and identify any goals you may have for your journey”, where “what we talk about is guided by you”. They say to expect that topics in this initial assessment may include “medications such as puberty blockers and hormone treatment” and “the possibility of storing sperm”. Their information page also recommends the Gender Minorities Aotearoa website, where as mentioned patients can find information on the ideal responses for ‘passing’ a mental health assessment. None of this gives the impression of a rigorous screening process.

Nor is medical transition restricted to adult patients, or even to older teens. Alarmingly, evidence suggests that some New Zealand doctors are starting under-16s on cross-sex hormones. Gender Minorities Aotearoa claim that cross-sex hormones are “usually prescribed from age 14 - 16” in New Zealand, although they warn that getting hold of these drugs can be “a little more complex” for children under the age of 16. Consistent with this, the New Zealand Guidelines for Gender Affirming Healthcare suggest that there may be “compelling reasons, such as final predicted height, to initiate hormones prior to the age of 16 years”. The New Zealand medical website Family Doctor even suggests that under “exceptional circumstances… people under 16 may be allowed to start [hormonal] treatment without the consent of their parents” (emphasis added).

We can hope that only an extreme fringe of doctors would willingly prescribe cross-sex hormones to children in their early teens. However, puberty blockers appear to be quite freely available to younger New Zealand children. Reports suggest that we have taken a particularly incautious approach to prescribing these medications. For example, it was not until September 2022 that our Ministry of Health begrudgingly removed a claim on its website that puberty blockers are “safe and fully reversible”. In contrast, the United Kingdom’s National Health Service revised similar guidance two years earlier, to highlight the potentially serious risks of these drugs.

Some activists and medical professionals characterise puberty blockers as a ‘pause button’. However, ‘accelerator pedal’ seems like a more accurate description since almost all children who take them progress to cross-sex hormones (usually at age 16).

A recent article in the Listener reported that 505 New Zealand children aged between 10 and 17 were prescribed puberty blockers in 2020. A few of these children may have been prescribed these drugs to treat conditions other than gender dysphoria. However, it’s reasonable to assume that for most of these children, these drugs were the first step towards medical transition.

While a significant number of gender questioning children take puberty blockers, the majority don’t seem to. Counting Ourselves found that in 2018, about 17% of self-identified trans and non-binary youth (aged 14 to 24) had been prescribed these drugs. This proportion has probably increased somewhat since then, given that the aforementioned Listener article reported that the number of children prescribed puberty blockers increased by 66% between 2017 and 2020.

Certain medical practices seem particularly enthusiastic about puberty blockers. One disconcerting example is Youth 298, a health centre in Christchurch that serves “vulnerable young people aged between 10 and 25”. Youth 298 has roughly 500 registered patients (a doctor from this clinic kindly provided me with this information by email). This medical practice has estimated that about 100 of their patients are “gender diverse”, and that about 65% of these are taking puberty blockers. This equates to about 13% of their entire reported patient population. In contrast, the Youth 298 doctor I contacted told me that most Christchurch general medical practices don’t prescribe puberty blockers. Parents would be well advised to choose their children’s doctors carefully.

In contrast with pharmaceutical treatments, surgical gender reassignment is difficult to access in New Zealand. Newshub states that only 15 genital reconstruction surgeries were performed within our public health system between 2020 and 2022. The article estimates that there is a twenty-year waiting list for these surgeries, despite the reported difficulty of being referred onto this list. This situation seems unlikely to be resolved in the near future, given that New Zealand’s public health system has extremely long waiting lists for other elective surgeries that address physical rather than psychological symptoms, and are arguably safer and more cost-effective. Even privately-provided gender surgery services are scarce in New Zealand. Dr Rita Yang of Wakefield Hospital in Wellington claims to be “New Zealand’s only specially trained Gender Affirmation surgeon” in a country of five million people.

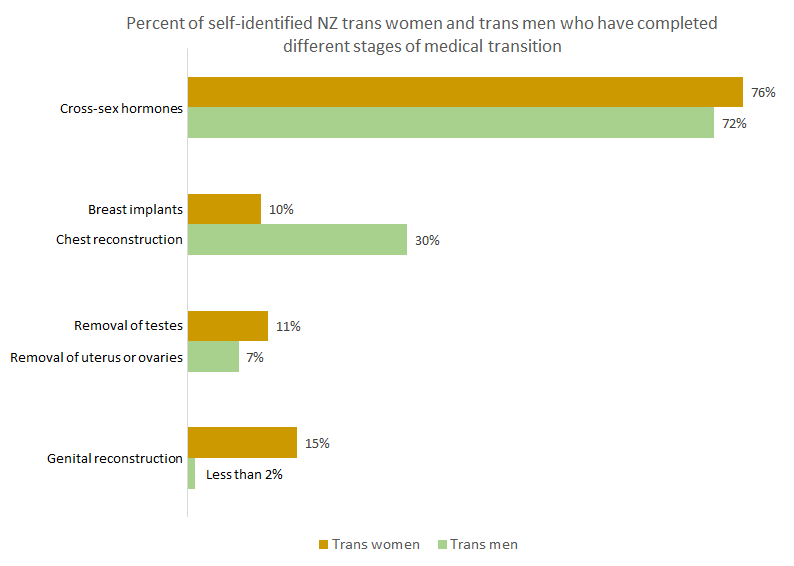

The chart below shows results from Counting Ourselves, which illustrate that taking cross-sex hormones is much more common than undergoing gender transition surgeries. The most frequent type of trans surgery appears to be chest reconstruction (i.e. surgical removal of the breasts). About 43% of patients who have received chest surgery report doing so through the public health system. Females who identify as trans often engage in breast binding, a practice that frequently causes chronic pain and shortness of breath. These symptoms may motivate these patients to seek treatment and help them to obtain priority on elective surgery waiting lists. Unfortunately, chest surgery itself often results in surgical complications and intractable pain.

Because hormones are easily accessible but surgery is not, many people complain that they are stranded part way through the transition process. Newspaper reports suggest that those who can afford it often pay for gender surgeries in Thailand, where prices are relatively cheap but surgical standards are inconsistent and uncertain. Consistent with these reports, Counting Ourselves estimates that over 80% of New Zealanders who obtain genital reconstruction surgeries do so overseas. The number who come to serious harm as a result appears to be unknown.

This is worrying, because genital reconstruction surgery is very technically challenging. Complications often occur even in top-ranked US research and teaching hospitals. Harper University Hospital reports that surgical-site infections occur in over 50% of patients who undergo genital reconstruction surgery. Similarly, a gender surgeon at New York University Langone Health recently admitted to the New York Times that surgical complications often occur. She comments that, “we wouldn’t accept this rate of complication necessarily in other procedures”. Catastrophic surgical failure has also occurred within Britain’s well-regarded National Health Service. We can only assume that surgery in Thailand’s poorly-regulated gender clinics is even more hazardous.

Our long surgical waiting list is the result of a huge increase in New Zealanders seeking medical transition. This increase has been largest among young people and natal females. The chart below shows that between 1990 and 1995, only one person sought female-to-male gender transition at Wellington Endocrine Service. By 2016, 41 people were seeking female-to-male gender transition in a single year. Moreover, over this time period the average age of female-to-male transitioners fell from 30 to 22 years old. This is roughly half the average age of New Zealand females (which is 39 years). The researchers note that children as young as 11 years old have started presenting to the Service.

Slightly newer data indicate that rates of medical transition continued to grow rapidly until at least 2018. A striking example is Waitemata District Health Board (DHB), which serves the northern part of the Auckland region. Waitemata DHB reported 11 “first appointments... for the purpose of receiving gender affirming medical care - which may include hormone therapy” in the 2015/2016 year. By 2017/2018, this had grown to 90 patients. Waitemata DHB noted that “these numbers may underestimate... the true number of people receiving hormone therapy, as some referrals are received by other services. These other referrals are not coded electronically”. Waitemata DHB states that the youngest patients referred are aged under 12 years. It refuses to provide these children’s exact ages, on the grounds that it would take too much time to find out.

We can get a sense of the size of this issue by comparing the number of people who sought gender transition to the size of the population served by each DHB. For example, Auckland DHB serves around 490,000 people. Based on this, we can estimate that 20 out of every 100,000 people served by Auckland DHB started ‘gender affirming care’ in 2018. Counties Manukau and Waitemata DHBs had slightly lower rates, at around 14 per 100,000 people. On the other hand, the equivalent rate for Capital and Coast DHB is much higher, at roughly 42 per 100,000 people. (This estimate is adjusted to exclude referrals from outside this DHB’s catchment area).

To put this into context, 46 out of every 100,000 people served by Capital and Coast DHB were hospitalised for traffic injuries in 2018. This is frequent enough that we don’t dismiss concerns about traffic accidents as irrational. Medical transition in New Zealand clearly occurs at a rate that deserves to be taken seriously.

Since 2018, our government has been working hard to improve the accessibility of medical transition. It thus seems possible that current rates of medical transition are even higher than those shown above.

We can estimate how many children are being transitioned by looking at the rate at which they’re taking puberty blockers. As mentioned earlier, 505 New Zealand children aged between 10 and 17 were prescribed puberty blockers in 2020. Stats NZ data indicate that there were 649,940 New Zealanders aged between 10 and 19 in that year. (I couldn’t find an exactly age-matched comparison group). This means that about 78 out of every 100,000 children in this age range were prescribed puberty blockers in 2020. This suggests that children and teens are being medically transitioned at a higher rate than adults.

We can also compare these rates of gender transition to international estimates of the number of people who attended gender clinics during the late 20th century. These studies typically found that each year, about 0.15 people per 100,000 population initiated treatment for gender issues (most of these were natal males). The 2018 rate of medical transition within Capital and Coast DHB was thus over 275 times higher than the rate reported by these early studies.

It’s hard to know how consistent the pattern of increased medical transition is across our country as a whole. For example, in 2018 and 2019 Official Information Act (OIA) responses, Canterbury and Nelson-Marlborough DHBs acknowledged that they don’t count the number of patients that they medically transition. Our Ministry of Health has likewise said that it does not track statistics on medical transition or transition regret.

In sum, youth medical transition is increasingly widespread in New Zealand. However, there is little proactive monitoring of its overall frequency, safety, or effectiveness. This is concerning, because many researchers and clinicians consider these medical interventions to be experimental and potentially dangerous.

How many people identify as trans?

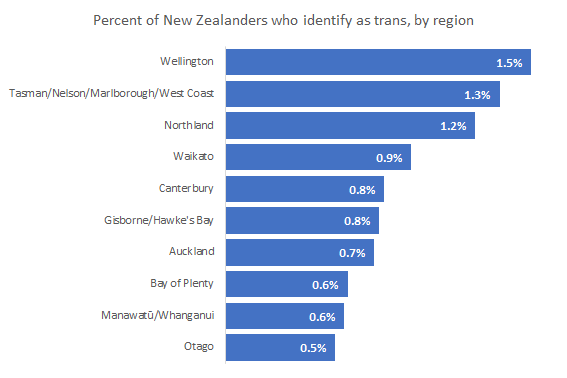

The pipeline for future medical transition consists of people who identify as trans. Stats NZ recently conducted New Zealand’s first nationally-representative survey of this group. The survey examined people who were 18 years or older, and took place over the year ending in June 2020. I’ve reanalysed this survey data to produce the results provided below.

Of the people surveyed by Stats NZ, 0.8% identified as trans or non-binary. More specifically:

0.6% of natal males identified as trans women.

0.5% of natal females identified as trans men.

0.3% of people (i.e. natal males and females combined) identified as 'another gender'.

Unfortunately, the survey didn’t ask whether people had medically transitioned, or whether they wanted to. However, since many trans-identified people eventually medically transition, the large size of this group suggests that rates of transition may keep rising in future.

Who is most likely to identify as trans?

The survey found that younger people were more likely to identify as trans or non-binary:

The survey also found considerable regional variation in the number of people identifying as trans. Otago has the lowest rate at 0.5%. Wellington has the highest rate at 1.5% (nearly double the national average). This seems consistent with the high rate of medical transition within Capital and Coast DHB (which provides services to Wellington).

What do these trends mean?

There will be many reasons for these patterns in who identifies as trans. Nonetheless, the impact of social influence is easy to recognise. Young people are known to be especially vulnerable to social influence. They are also more likely to be heavy users of social media sites like Tumblr that are known for promoting trans identities. Similarly, Wellington is a small capital city dominated by public servants, and is widely regarded as “the wokest city in New Zealand”. This creates an environment where ‘being trans’ is celebrated and encouraged, and critical thinking about the trans wave is unwelcome.

Social influences of some kind are also the only plausible explanation for the dramatic increase in people seeking medical transition, other than unlikely theories about microplastics in the water.

Some people characterise these social influences as a positive force. They argue that rising rates of trans identities and medical transition reflect greater acceptance of diversity. This is said to allow young people to express their true selves and flourish. If this were the case, we would expect the trans wave to be accompanied by improving youth mental health. The reality is exactly the opposite. As rates of transition have soared, so too have rates of mental health issues among both young people overall and LGBT individuals in particular. To illustrate this trend, the chart below shows data on first appointments for ‘gender affirming care’ in Wellington, compared with rates of psychological distress among New Zealand youth. As the chart shows, the trans wave has happened in concert with a tripling in rates of youth psychological distress. This evidence is hard to reconcile with the belief that the social influences causing increased transition are entirely beneficial.

What explains our rising rates of trans identities and medical transition?

Numerous clinicians and researchers recognise that the social influences causing the trans wave are not entirely positive. In her excellent essay in Skeptic magazine, eminent social psychologist Carol Tavris argues that young people are being encouraged to misinterpret psychological distress as a sign that they must be trans:

Adolescence is rarely an easy time, but life for most American teenagers now is more difficult than it has ever been, as rising rates of depression, anxiety, and body dysmorphia indicate. In a world where “gender identity” has become such a dominant theme, infusing language, art, and politics, where young people struggle to decide if they are cis, gay, other, pan, a-, or some combination, no wonder it has become the explanation du jour of the difficult miseries of adolescence — anxieties exacerbated by COVID, climate change, the economy, school costs, and uncertain futures. Saying you suffer from “gender dysphoria” is cool and common, just as saying you were sexually abused in your youth once was. It explains everything. It gets attention and support. Sometimes gender dysphoria is the explanation; statistically, given the tiny percentage of actual transgender people in the population, far more often it isn’t.

This interpretation of the trans wave provides a clear explanation for why psychological distress and gender transition have risen in tandem. It is also consistent with other relevant evidence. For example, we know that young people suffering psychological distress are much more likely to seek medical transition. This applies even if their early childhood behaviour was entirely sex-typical and they have shown no prior signs of identifying with the opposite sex.

A recent study also found that the most common reason people gave for reversing medical transition was realising that their desire to transition had been caused by “other issues”. In other words, they realised that they had misinterpreted general psychological distress as a sign of ‘being trans’. Their confusion is understandable, because children are being taught to believe that a combination of psychological distress and discomfort with traditional sex stereotypes indicates ‘being trans’. Since few people feel entirely comfortable with sex stereotypes, anyone who truly holds this belief will be vulnerable to misinterpreting psychological distress as gender dysphoria. This phenomenon is powerfully illustrated by the documentary film The Detransition Diaries, in which three courageous and insightful young women explain why they decided to transition, and the devastating consequences.

Other factors may also have contributed to the simultaneous rise in rates of psychological distress and gender transition since 2011. Increased social media use may be contributing to both trends. Social media has been linked to increased psychological distress among young people, and some social media content also promotes gender transition. Additionally, the rise of social messages that destabilise young people’s identities may be directly contributing to both increased rates of transition and deteriorating mental health.

The trans wave is undoubtedly causing serious physical health costs, leaving numerous patients in chronic pain. Trans activists argue that these physical health costs are outweighed by supposed mental health benefits. The evidence we’ve seen suggests that this is doubtful. Our increased rates of youth gender transition may be causing much more harm than benefit.

Where are we heading?

New Zealand is at a crossroads in how it approaches youth gender transition. Sceptics are probably right to doubt that this issue is as extreme here as in the United States, where gender surgeons advertise their services on TikTok. However, we seem to be following in that country’s footsteps.

A recent Pew Research survey found that an astonishing 5.1% of US adults under 30 identify as trans or non-binary. This compares with about 1.6% in New Zealand. ‘Greater acceptance’ can’t explain this difference unless Americans are three times as accepting of diversity as Kiwis. This seems unlikely, since survey data show that Kiwis are significantly more accepting of trans people than their US counterparts. A more plausible explanation is the widespread and sometimes extreme promotion of trans identities in US schools. As our own schools introduce lessons and policies that encourage trans identities, we could easily see rates of trans identities similar to those in the US. This seems likely to contribute to even higher rates of medical transition.

European countries have generally been slightly more cautious about embracing the trans wave than the US. In the UK, the risks of youth gender transition have been regularly highlighted by prestigious mainstream media outlets like the Times, the Economist, the BBC, the Observer, and occasionally even the Guardian. Stephanie Davies-Arai of Transgender Trend, who has been repeatedly smeared as ‘transphobic’ for raising the alarm about youth gender transition, was recently named in the Queen’s Birthday Honours list for services to children. New Zealand needs similarly critical and informed media coverage of the trans wave. We also need more people from all walks of life to speak out about this issue.

European healthcare providers are becoming wary of youth medical transition. Finland and Sweden have both strictly limited the availability of these treatments. The French National Academy of Medicine has issued a statement urging caution. The Tavistock clinic, which is the UK’s leading gender clinic for children, is being closed down over concerns that its services are “not a safe or viable long-term option” for the treatment of gender questioning youth. The Tavistock clinic is also being sued for criminal negligence. Lawyers for the affected families claim that patients were “rushed into taking life altering puberty blockers without adequate consideration or proper diagnosis”, resulting in “physical and psychological permanent scarring”. The Times described the reasons for the closure of the Tavistock in a devastating leading article:

The damage done is immeasurable. No one knows how years of ideological dogma, inappropriate treatment and a culpable failure to consider the overall mental welfare of the children treated by the Tavistock Clinic will affect the thousands referred to its Gender Identity Development Service... It naively confused sexual orientation with gender identity, accepted at face value all declarations by children that they were born in the wrong body and treated all complex problems through the prism of gender.... Whistleblowers were denounced as transphobic.... When at last the NHS decided to investigate, the report by Dr Hilary Cass was appalling. The clinic had failed to keep accurate records of all the children treated with hormones after they grew up. There was no long-term monitoring of the outcomes, no attempt to look at other factors affecting mental wellbeing, and no distinction between clinical experience and the shrill activism of those who insisted that trans rights were above all a matter of social and political acceptance... Worries about the Tavistock’s obtuse ideology have long been highlighted by writers for The Times. At last the government has listened.

The similarities between the Tavistock clinic and New Zealand’s health system are striking. In both the UK and New Zealand, ideologically-motivated pressure groups have had an undue influence on medical practice. In both countries, there has been a distinct lack of monitoring, followup, and evaluation of medical transition. In fact, recent comparisons have found that the prescription of puberty blockers is “less controlled” and more than ten times as frequent in New Zealand than in the UK.

As the Times article describes, the UK government eventually took notice of public outcry. They organised an independent review by paediatrician Hillary Cass, which led to the closure of the Tavistock clinic. The Tavistock review suggests a useful way forward for our country. We need someone with Dr Cass’s courage, compassion, and scientific integrity to examine how our health system is treating gender identity concerns. I have every confidence that this will happen eventually. The scale of the damage to our children will one day be revealed to all New Zealanders.

We still have the opportunity to adopt a more science-based, more humane, and less ideological approach to supporting gender questioning youth. If we don’t take action now, we will be counting the costs to our children’s health for decades to come. History will judge those who stood up for what was right, and those who did not.

New Zealand parents can find information on how to ask schools to exempt their children from lessons that encourage trans identification here.

All charts shown in this article are based on data from university-based research or official statistics, and can be independently verified by accessing the links provided.

This article was first published on 24th November 2022, and slightly updated in April 2024 with a clearer title, a new title image, and information about survey data comparing acceptance of trans people in New Zealand with the US.

Thank you for this information. I make 2 ancillary points:

Firstly: the use of hormone blockers to prevent the onset of puberty is not an approved use in this country. PHARMAC records overall figures for the drug but does not distinguish approved from unapproved use. This disguises the extent of uses of Blockers. While requiring recording the unapproved use of medicines may be difficult it should be required; not least because in a system of tax based funding we all pay for, or at least subsidise use.

Second: MOH, as you say, provides an extensive list of transition surgeries provided by the our publicly funded health service, but in practice funds very few surgeries. The young person, as you say, may embark on transition possibly believing they will get surgery for free. There is however only one practice providing these surgeries. These young people go onto the long public waiting list, but find themselves stuck waiting in limbo. They then have to option of paying for the same service from the same provider privately. Hence the numbers of youngsters pleading for money to fund transition on the internet, and enormous pressure on parents to pay the significant costs involved.

IN EFFECT THE PUBLIC SYSTEM HAS ORGANISED THE CLIENT LIST FOR THE PRIVATE BUSINESS. JUST LIKE IVF THIS BARNCH OF MEDICINE BECOMES HUGLY PROFITABLE FOR PRIVATE HEALTH PROVIDERS. I AM SURE YOU KNOW COUPLES MORTGAGE THE HOUSE FOR IVF. NOW THE SAME PRESSURES WILL BE PRESSED INTO SERVICE TO PAY FOR TRANSITION.

Holy smoke, Laura - a smoking gun indeed! Thanks for your detailed investigation, it will be most useful.